To start this guide, download this zip file.

Variables

Consider the following code:

def paint_green(bit):

while bit.can_move_front():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')This tells Bit to keep moving and painting green as long as the front is clear. So Bit will paint an entire row or column green, depending on which direction it is facing.

But what if we also want to paint rows and columns red? And yellow and green and brown and blue?

We would need to write a separate function for each one! Not great!

Functions can have multiple parameters

Never fear, it turns out that functions can take multiple parameters:

def go(bit, color):

""" Given a bit and a color, move and paint that color until blocked """

while bit.can_move_front():

bit.move()

bit.paint(color)The go() function takes two parameters:

- a Bit

- a color

Inside the go() function, the variable called bit is equal to the Bit, and

the variable called color is equal to whatever color you give it. You can see

this in action using the file called go_color.py in the zip file above:

from byubit import Bit

def go(bit, color):

""" Given a bit and a color, move and paint that color until blocked """

while bit.can_move_front():

bit.move()

bit.paint(color)

@Bit.empty_world(5, 3)

def lots_of_paint(bit):

""" Paint colors until blocked """

go(bit, 'red')

bit.turn_left()

go(bit, 'green')

bit.turn_left()

go(bit, 'blue')

if __name__ == '__main__':

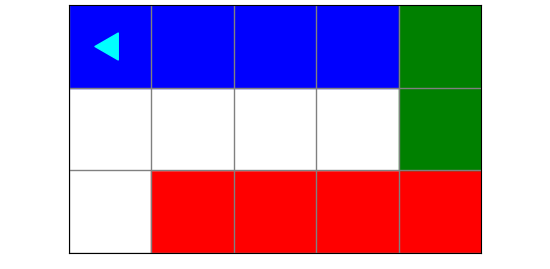

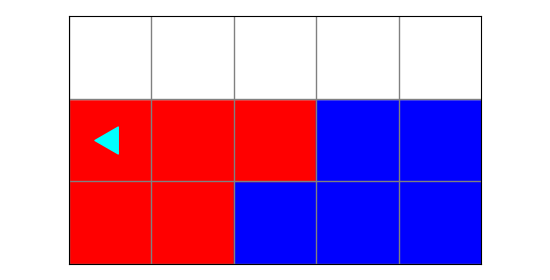

lots_of_paint(Bit.new_bit)Bit starts in an empty 5x3 world. It does the following:

- paints a row red

- turns left

- paints a row green

- turns left

- paints a row blue

The result is this world:

Parameters become variables in a function

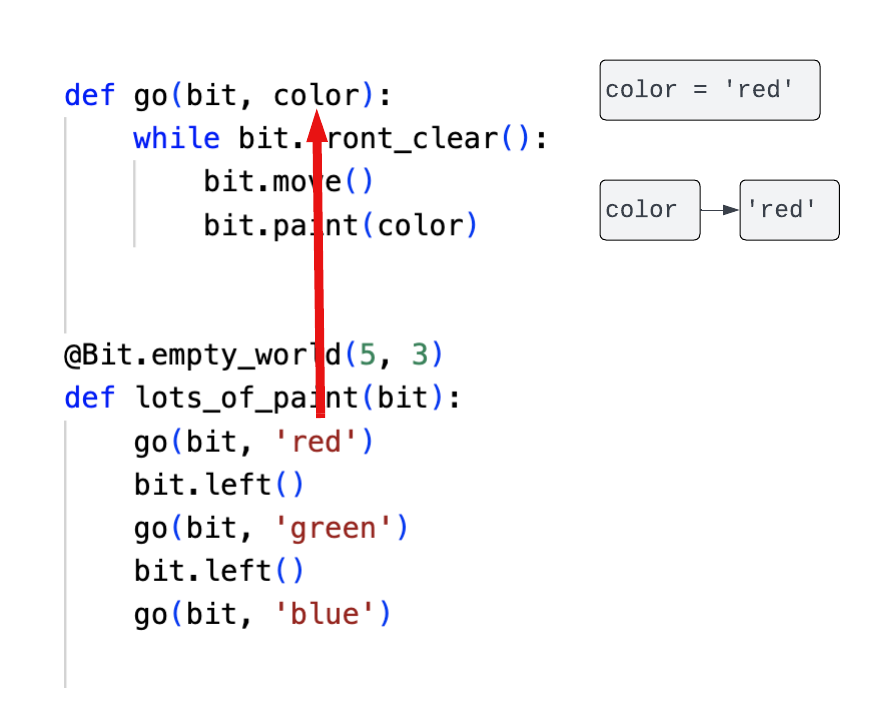

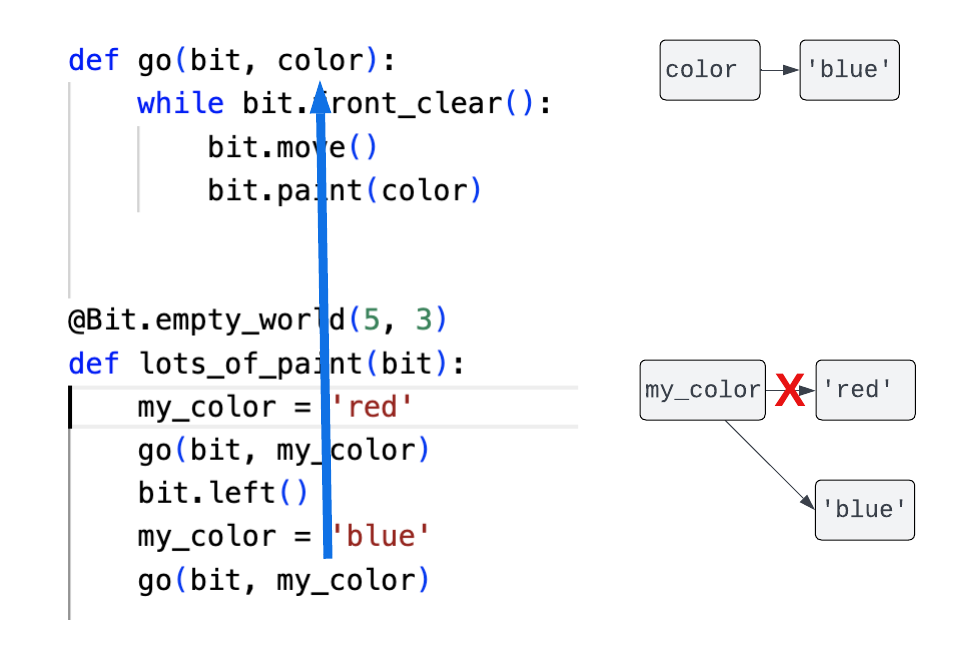

To see how parameters to a function work, look at this diagram:

The first time this code calls go(), it uses 'red' as the second parameter.

This means that inside the go() function, there is a variable called color

that is equal to the string 'red'.

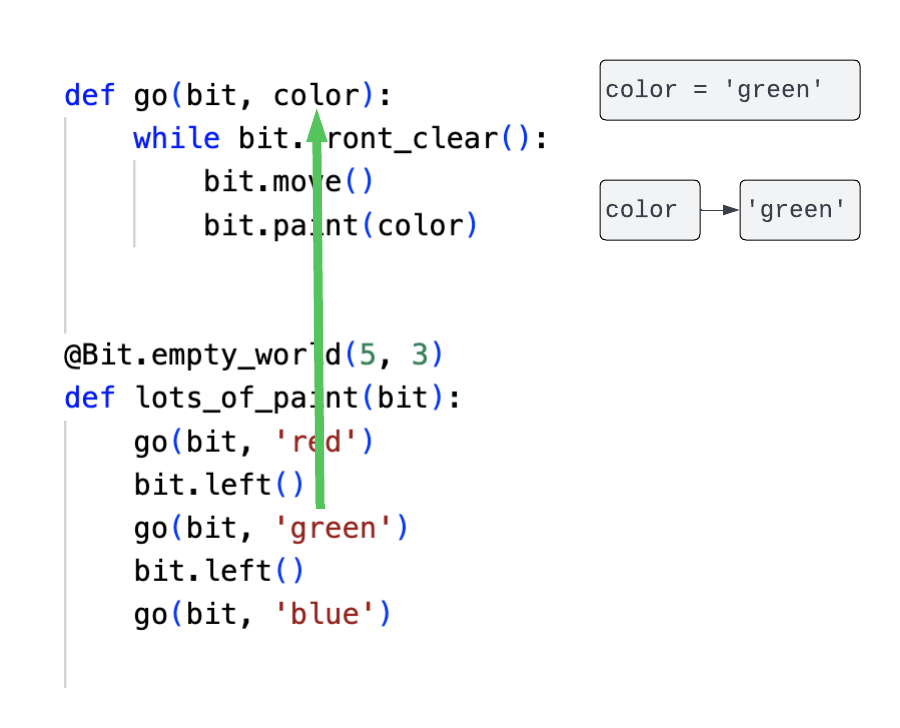

The second time this code calls go(), we have this situation:

This time, the code uses 'green' as the second parameter. This means that

inside the go() function, the variable called color is equal to the string

'green'.

Notice that we use the notation color → 'red' and color → 'green' in this

pictures. This indicates that a variable has a name (color) and it references

a value (‘red’ or ‘green’). The value of a variable can change over time.

Changing the value of a variable

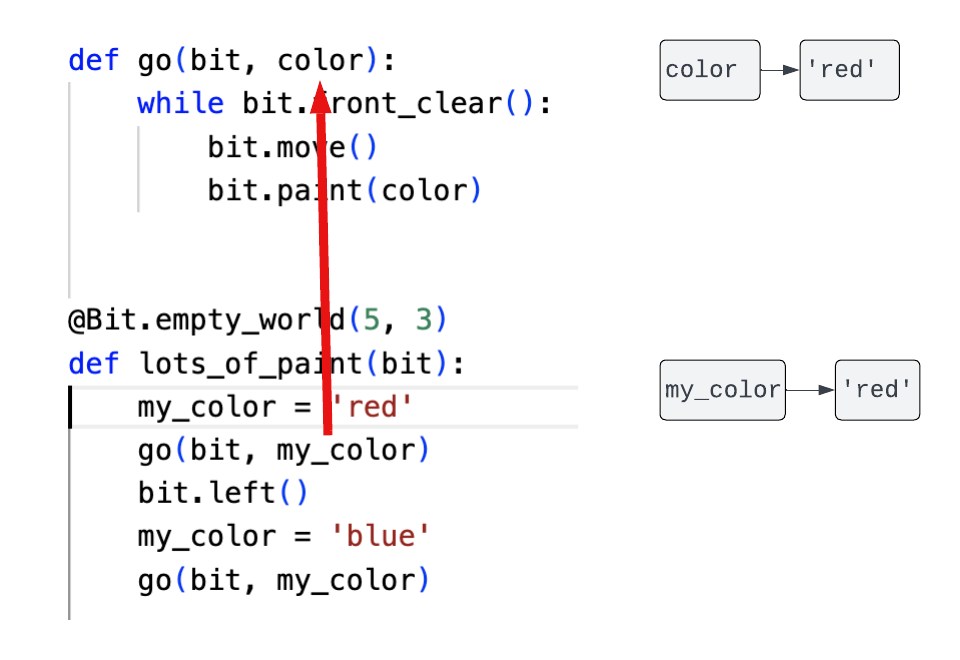

You can change the value of a variable any time using this syntax:

my_color = 'red'Here, the variable is called my_color and its value is 'red'. Using our

notation, my_color → 'red'.

Then you can call functions using this variable:

my_color = 'red'

go(bit, my_color)

my_color = 'blue'

go(bit, my_color)The first time, my_color → 'red' and so inside go(), color → 'red'.

The second time, the value of my_color changes, so now my_color → 'blue'

and inside go(), color → 'blue'.

Painting with different colors

You can see this in action with the file called color_variables.py in the zip

file above:

from byubit import Bit

def paint_two(bit, color):

bit.paint(color)

bit.move()

bit.paint(color)

def paint_three(bit, color):

paint_two(bit, color)

bit.move()

bit.paint(color)

@Bit.empty_world(5, 3)

def run(bit):

first_color = 'red'

second_color = 'blue'

paint_two(bit, first_color)

bit.move()

paint_three(bit, second_color)

bit.turn_left()

bit.move()

bit.turn_left()

paint_two(bit, second_color)

bit.move()

paint_three(bit, first_color)

if __name__ == '__main__':

run(Bit.new_bit)Here we have a function called paint_two(bit, color) that takes two

parameters, a bit and a color. It does this:

- paint the color

- move

- paint the color

We have another function called paint_three(bit, color) that takes the same

two parameters. It does this:

- call

paint_two() - move

- paint the color

This allows it to paint three colors.

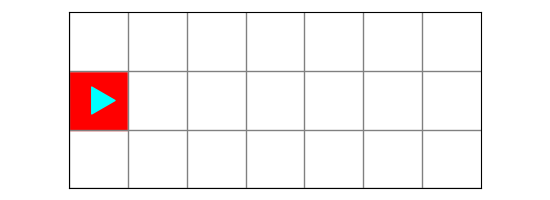

Finally, we have two variables: first_color → 'red' and

second_color → 'blue'. We use these two variables when we call the functions,

so that we can:

- paint two blue squares (using

first_color) - paint three red squares (using

second_color) - turn around and go to the next row up

- paint two red squares (using

second_color) - paint two blue squares (using

first_color)

Run this code and see the result:

Getting the current color

Bit has a useful function called get_color() that lets you get the color of

Bit’s current square so you can store it in a variable. For example:

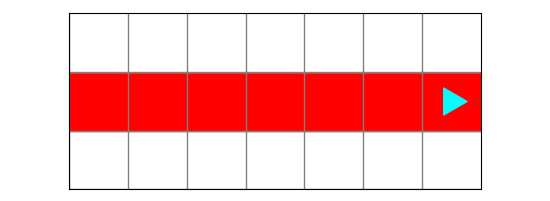

found_color = bit.get_color()Consider the following problem. Bit is in a world with one color:

Bit’s job is to find out what color this is and then fill in the rest of the row with that same color:

But Bit doesn’t know what color it is going to have in that first square. It might be blue:

Look a the file called fill_a_color.py to see how to do this:

from byubit import Bit

def go(bit, color):

while bit.can_move_front():

bit.move()

bit.paint(color)

@Bit.worlds('color1', 'color2')

def fill_a_color(bit):

found_color = bit.get_color()

go(bit, found_color)

if __name__ == '__main__':

fill_a_color(Bit.new_bit)In fill_a_color(), Bit first gets the current color and stores it in a

variable called found_color. It then uses found_color when it calls go().

Run this code and use the buttons to see that it solves both worlds. In the

first world, bit.get_color() returns 'red', and so found_color → 'red'. In

the second world, bit.get_color() returns 'blue', and so

found_color → 'blue'.